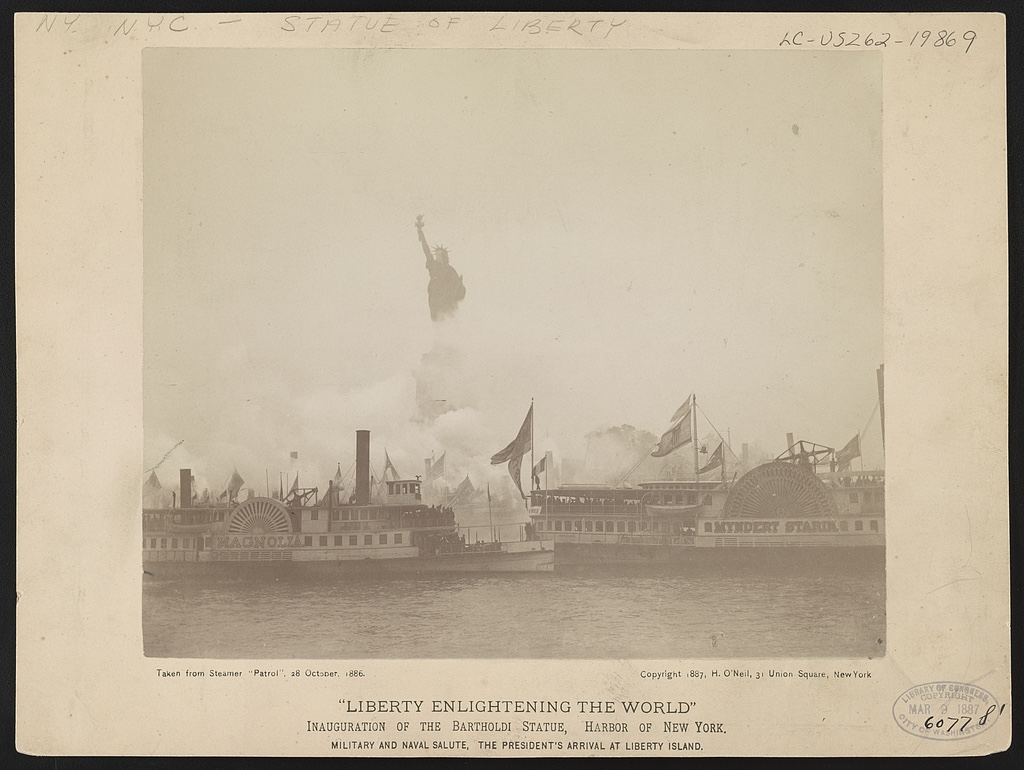

On a rainy late October day in 1886, New Yorkers gathered in anticipation for the unveiling of the nation’s “New Colossus.” After years of planning and labor, the monument now stood tall on Bedloe’s Island. Thousands crowded on both land and sea to get a look at “Liberty Enlightening the World” — better known as the Statue of Liberty.

Proposed in 1865 by French politician and abolitionist Édouard de Laboulaye, Lady Liberty was a gift from France to the United States as a symbol of friendship between the two countries and a commemoration of American independence. But war in Europe and a series of fundraising woes in the United States delayed the monument’s arrival by two decades. The final push came from a fundraising campaign by newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer. Through his newspaper, the New York World, Pulitzer raised the needed capital to complete the statue’s pedestal. At last, on October 28, the Statue of Liberty was ready for its dedication and big reveal.

Despite the dreary autumn weather, the Statue of Liberty’s dedication was a monumental affair. New York City declared the day a general holiday, and Brooklyn, an independent city at the time, closed its schools. Festivities began at Madison Square Park, where the statue’s arm and torch had been displayed from 1876 to 1882 to raise funds. From the park, a procession traveled downtown, and during the final mile between City Hall and the Battery, workers threw ticker-tape from their windows to celebrate the statue’s dedication, marking the first occasion of what would become a beloved New York tradition. (More on that history here.)

After the procession, President Grover Cleveland sailed to Bedloe’s Island for the official ceremonies. A water parade made up of 300 ships ranging from tugboats to large steamers followed, though unfortunately for the onlookers on land, inclement weather made it difficult to view the string of vessels.

On Bedloe’s Island, the Statue of Liberty waited for her moment, her face covered behind a tricolored French flag. Though, she didn’t have long to wait: the statue’s sculptor, Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, mistakenly pulled the rope off-cue, prematurely revealing Lady Liberty’s face to an excited public. President Cleveland formally accepted the statue on behalf of the American people, and the ceremony closed in a symphony of noise.

For all of the day’s grandeur, there was an underlying sense of irony. As suffragist Lillie Deveraux Blake put it: “The earth and the sea trembled with the mighty concussions, and steam-whistles mingled their shrill shrieks with the shouts of the multitude —all this done by men in honor of a woman.”

Indeed, the Statue of Liberty was constructed and celebrated against a backdrop of civil discourse and inequality in the United States. Of the more than 2,000 attendees to the formal dedication on Bedloe’s Island, only two women were invited. Blake and members of the New York State Women’s Suffrage Association (NYSWA) were not permitted to attend events on the island because of their unchaperoned status. In protest of not only the day’s events but of the limited liberties afforded to women, Blake and the NYSWA chartered their own boat and hung banners in defense of women’s rights.

Women were not the only group in the United States who found the symbol of freedom wanting. The Cleveland Gazette, a Black-owned newspaper, wrote of the statue’s dedication: “It is proper that the torch of Bartholdi’s statue should not be lighted until this country becomes a free one in reality. ‘Liberty Enlightening the World’ indeed. The expression makes us sick.” The idea of liberty being celebrated with the statue was a contradiction when the growing presence of racial injustice continued to affect the rights and liberties of Black Americans.

Since the Statue of Liberty’s dedication, she has stood as a symbol of liberty and freedom. Still, from this colossal reminder, she also exposes the contradictions of American liberty — contradictions that continue to shift and evolve with each generation.

Theresa DeCicco-Dizon is a public historian and museum educator based in New York City.

main photo: Joe Thomas