In the depths of New York Harbor’s salt-stung, restless waters lie some of the city’s oldest inhabitants: the Crassostrea virginica, better known as the Atlantic or Eastern oyster. These tough-shelled bivalve mollusks have lived here for roughly 10,000 years — and without them, New York City might never have become the metropolis we know today.

Long before Henry Hudson in 1609 sailed up the river that would later bear his name, the oyster was a staple food of the Lenape, the first people of the greater New York City area. In fact, the Lenape introduced Hudson to his first oysters. The Lenape consumed the mollusks in such abundance that they left behind massive piles of shells, known as middens, throughout the region. (In 1985, one such midden was discovered at the base of the Statue of Liberty on Liberty Island, which Dutch settlers once called the “Great Oyster Island” because of the plentiful oyster beds in the surrounding waters of New York Harbor.)

The Dutch began to settle in Lower Manhattan in the early 1600s, transforming Manhattan’ southern tip into a colonial port town called New Amsterdam. Oysters were a prominent feature of New Amsterdam, and though the Dutch were initially disappointed in the Eastern oyster’s inability to reproduce pearls, the settlers ultimately delighted in the bounty of bivalves that surrounded Manhattan’s shores.

Oysters were so omnipresent, they ended up making a mark on the city’s early infrastructure. Paerlstraat, today’s Pearl Street, was named after one of the many shell middens that could be found in the area. The street itself would later be paved with oyster shells.

By the mid-1600s, Lower Manhattan came under British control and was renamed New York. Yet oysters remained a fixture of colonial life. As the young city’s population grew, so did the need for public and private buildings. Oyster shells were burned to create lime paste, an essential ingredient in the mortar used to build the growing city. In 1697, an order was placed for “oyster shell lime” to construct Trinity Church, one of downtown’s longest-standing structures. (Sadly, eager oyster shell viewers won’t see evidence of that today, as the church was rebuilt following the American Revolution.)

Colonial New Yorkers continued to feast on the cheap and accessible mollusks, and taverns capitalized on this booming industry. One such tavern was Fraunces Tavern at 54 Pearl St., where oysters became the centerpiece of their offerings. Growing demand eventually led to one of the first formal efforts to prevent overharvesting. In 1715, the colonial government passed an ordinance banning oyster harvesting during the months without an “R” — from May 1 to September 1.

After the American Revolution, New York City transformed into a commercial and cultural powerhouse, and oysters followed New Yorkers into this new era. The oyster industry grew rapidly. As historian Mark Kurlansky wrote in “The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell”:

Before the 20th century, when people thought of New York they thought of oysters. This is what New York was to the world- a great oceangoing port where people ate succulent local oysters from their harbor. Visitors looked forward to trying them. New Yorkers ate them constantly. They also sold them by the millions.

Finding an oyster seller was as commonplace as your local New York bodega. Oyster carts lined the city’s streets, and eateries known as oyster cellars sprang up, giving New Yorkers their fill of the tasty delights. One celebrated cellar was Downing’s Oyster House at 5 Broad St. Run by African-American entrepreneur and abolitionist Thomas Downing, he served the shelled creature in many forms, from scalloped to fried. In 1842, New Yorkers enjoyed an estimated $6 million worth of oysters. By 1880, the city farmed about 700 million oysters, making New York the world’s oyster capital.

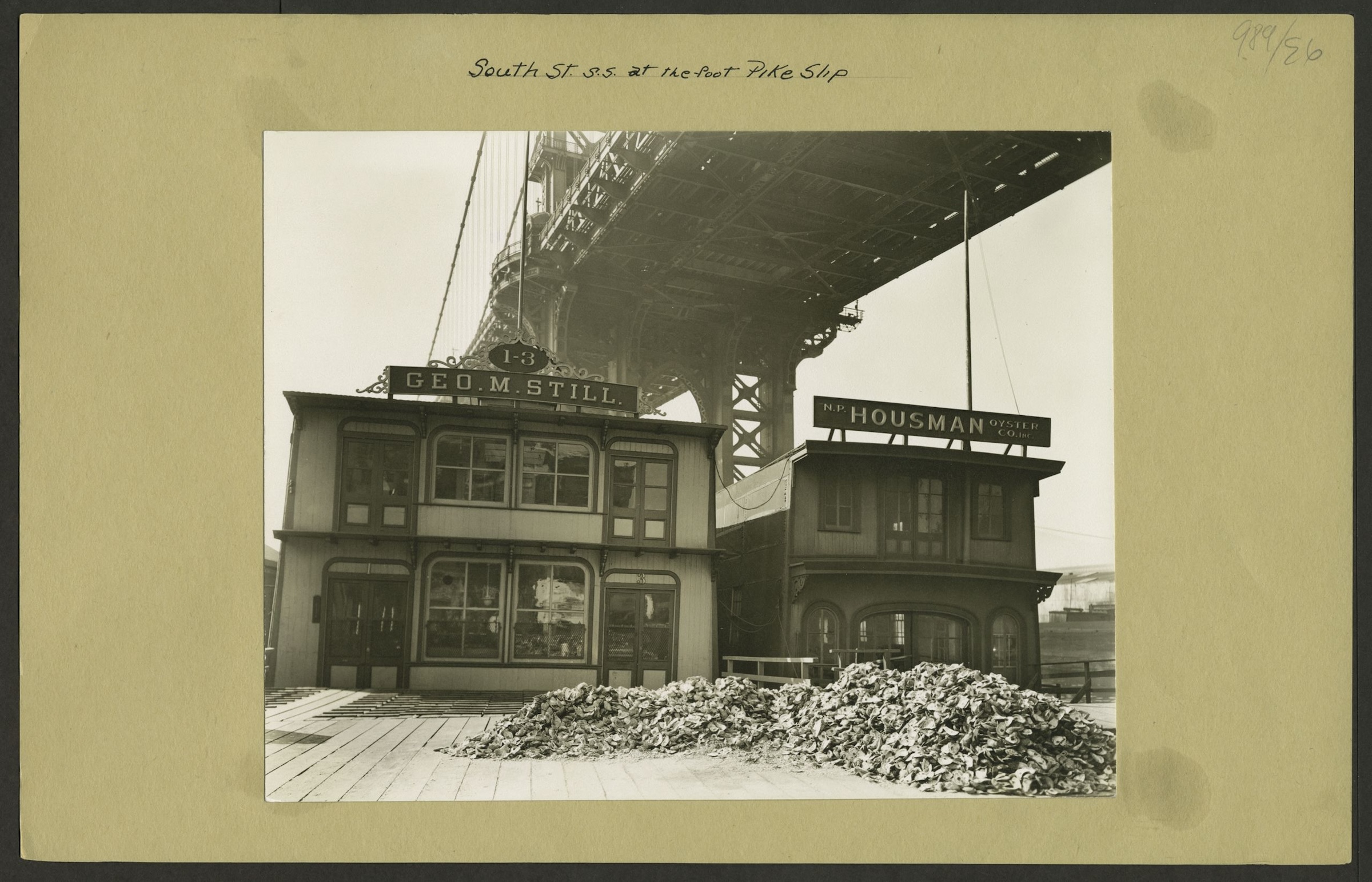

As New York City continued to progress and industrialize, its oyster population sharply declined, and what was once one of the city’s largest industries came to an abrupt halt. By 1906, the New York Harbor was virtually lifeless due to the ship traffic and industrial waste that polluted the water. In 1927, the city’s last commercial oyster farm closed its doors. Yet hope remains for the New York oyster. Conservation efforts with present-day groups like the Billion Oyster Project aim to restore the harbor’s oyster population through education and habitat restoration.

Indeed, from Pearl Street to the shells that wash up on the harbor’s shores, the oyster still makes its presence known in and around New York City.

Theresa DeCicco-Dizon is a public historian and museum educator based in New York City.

main image: iStock