The pursuit of racial equality and justice requires, among many things, an ongoing education — which is why, for Black History Month, we’re taking a look at the places in Lower Manhattan that illuminate the stories of the African diaspora.

From the blights on our country’s past to modern works of art that perhaps give hope for the future, the 10 following stories will help you discover more about Black history and culture.

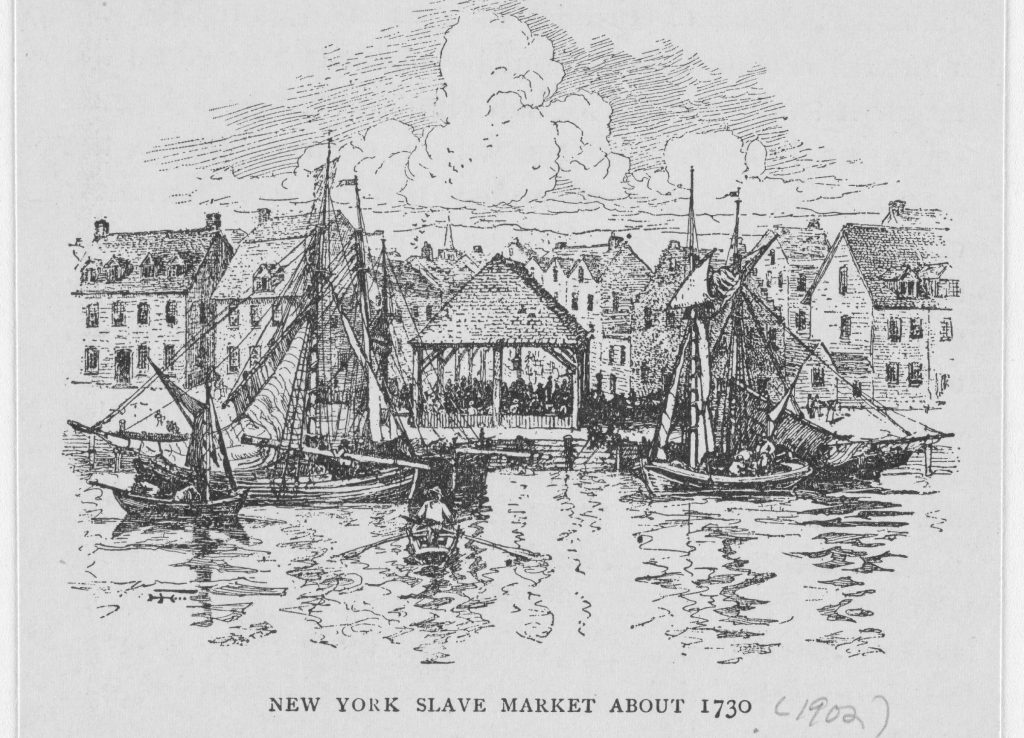

New York Slave Market

New York City was integral to the European slave trade in the 17th century, a grim origin point that has continued to impact the city and its people. By the eighteenth century, the city’s merchants, countinghouses and other institutions were all implicated in the slave trade, supplying enslaved people to the plantation colonies of the West Indies. Within the city, too, the enslaved population was used to build New York City’s infrastructure and provide unpaid labor. Here on Wall Street, between Pearl and Water streets, the Common Council of New York City on November 30, 1711 established a slave market. It functioned as one of the central hubs in the buying and selling of the enslaved African people whose very dehumanization helped build the city.

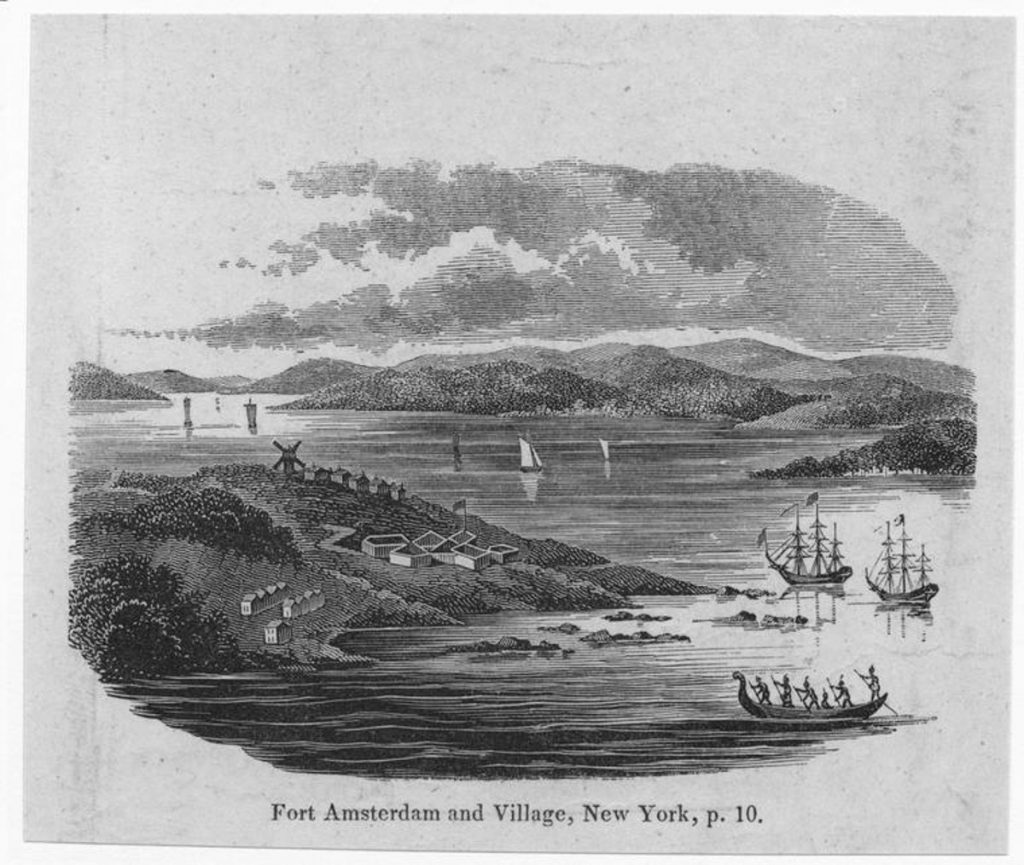

Fort Amsterdam/Fort George

The site of the U.S. Custom House, now the National Museum of the American Indian, was also once the location of the Dutch West India Company’s home to Fort Amsterdam, which was built in part by enslaved Africans. Later, that same site was renamed Fort George by the British. In 1741, a series of suspicious fires here convinced the city’s white elites that enslaved Africans and poor whites were joining forces against them. But the main witness to this supposed conspiracy was unreliable, and confessions were largely made by imprisoned suspects under duress. Despite this, city leaders executed many enslaved Africans and poor whites for their reported involvement.

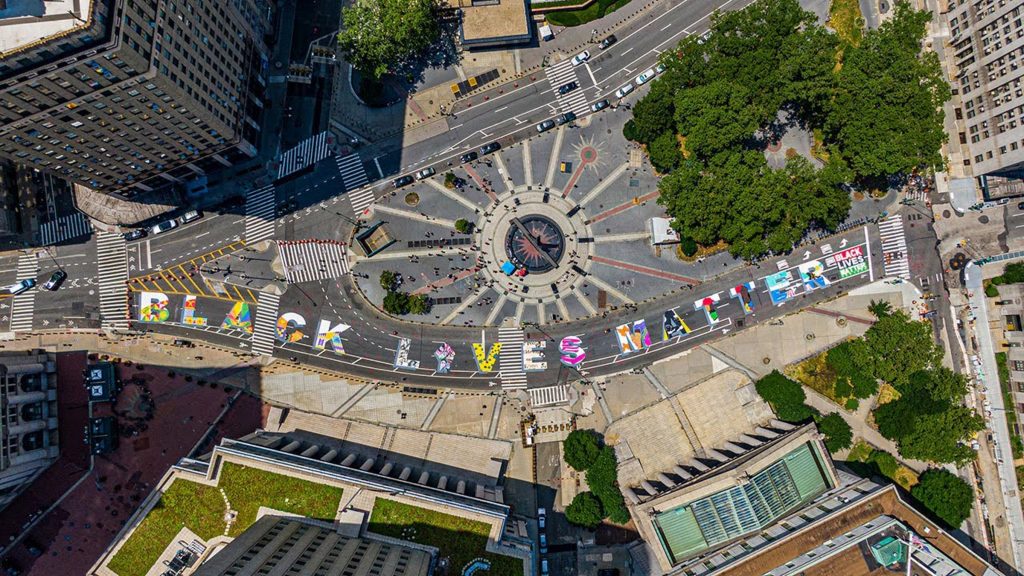

Civic Center Foley Square

Foley Square is now home to the Municipal Building, United States Courthouse and the New York State Supreme Court. Before the square was created in the early twentieth century, though, the area was the Five Points, a 19th-century neighborhood located at a five-way intersection. The neighborhood, which became infamous for its difficult living conditions, provided jobs and cheap rents for newly-emancipated Black communities, newly-arrived Irish immigrants, and the longer-established Anglo-Dutch working class. Centuries earlier, the Foley Square area had also been the site of a Native American village. In 2011, it became a site for the Occupy Wall Street protests. Most recently, in the summer of 2020, Black artists installed a Black Lives Matter mural here, a federal courthouse-adjacent reminder of systemic racism in the criminal justice system.

Foley Square

In 1741, dozens of people were convicted and brought to Foley Square after allegedly participating in the Great Negro Plot, a purported conspiracy by enslaved people and poor whites to start fires across what is now Lower Manhattan. Historians have debated whether or not such a plot even existed; regardless, 17 Black (and 4 white) people were hanged, 13 were burned at the stake, and 72 were banished from the colony.

Elizabeth Jennings

On July 16, 1854, Elizabeth Jennings, a young Black school teacher, church organist and activist, was forcibly removed from a streetcar belonging to the Third Avenue Railroad Company. Jennings and her friend Sarah E. Adams were initially permitted on the streetcar at the corner of Pearl and Chatham Streets, but the conductor grew confrontational. Together with the driver and a police officer, he forced Jennings and her friend out of the car. Jennings filed a successful lawsuit, which eventually paved the way for the end of segregated public transit in New York.

Tontine Coffee House/Slave Market

Before the Stock Exchange found its permanent home, stock brokers would meet and trade in a room at the Tontine Coffee House at the corner of Wall and Water streets. The Coffee House, which no longer exists, also served a more nefarious purpose: it was a local anchor for the transatlantic slave trade. Here, slave ship owners would register the enslaved Africans they had transported. Enslaved people were then bought and sold at a slave market between Pearl and Wall Streets, which was established by the Common Council of the City of New York in 1711. The city’s businesses, banks, insurance companies and the stock exchange were all implicated in the slave trade.

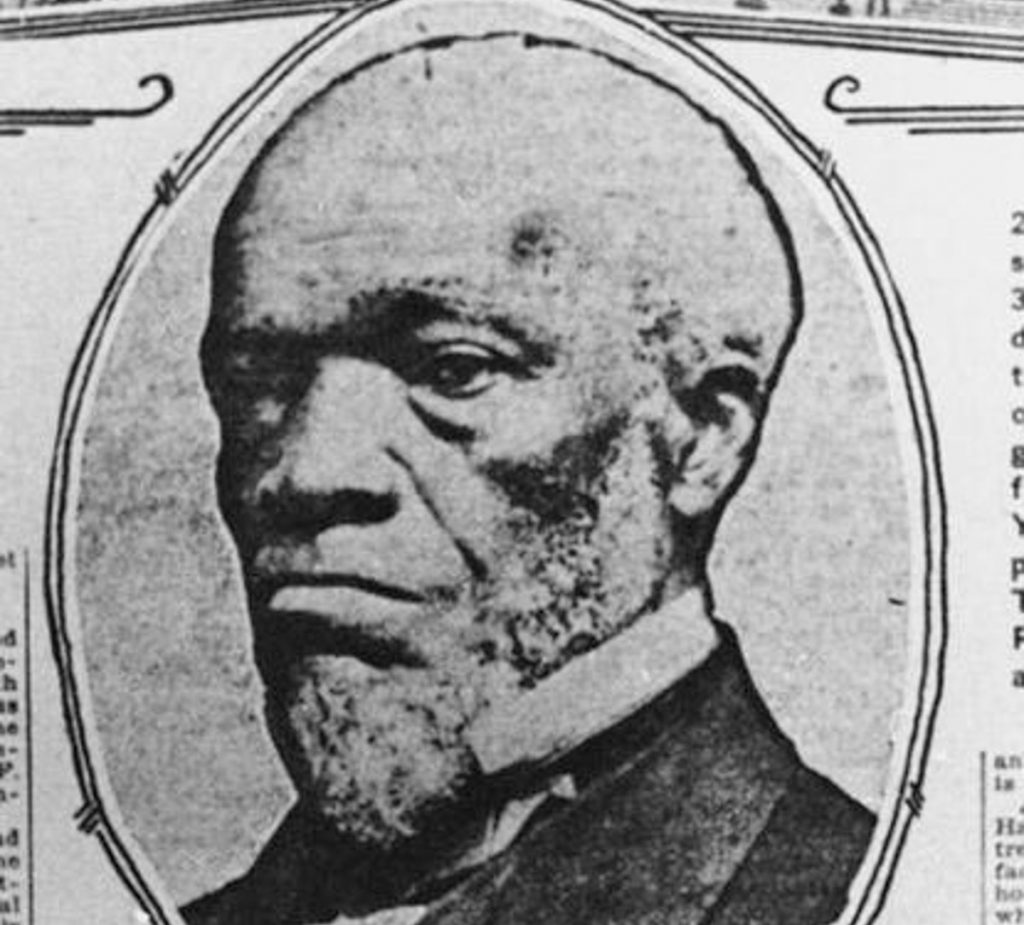

The Thomas Downing Portrait

Back in 1825, the 5 Broad Street address on this larger site was home to Downing’s Oyster House, founded by abolitionist and early restaurateur Thomas Downing. Born to a couple who were formerly enslaved, Downing elevated oysters from an everyman food to fine dining fare served to New York City’s elite. When Charles Dickens visited the city in 1842, Downing was selected to cater the “Boz Ball” in his honor.

Downing, who helped found the United Anti-Slavery Society of the City of New York, used the restaurant’s cellar as a stop on the Underground Railroad to harbor refugees and freedom seekers from the South.

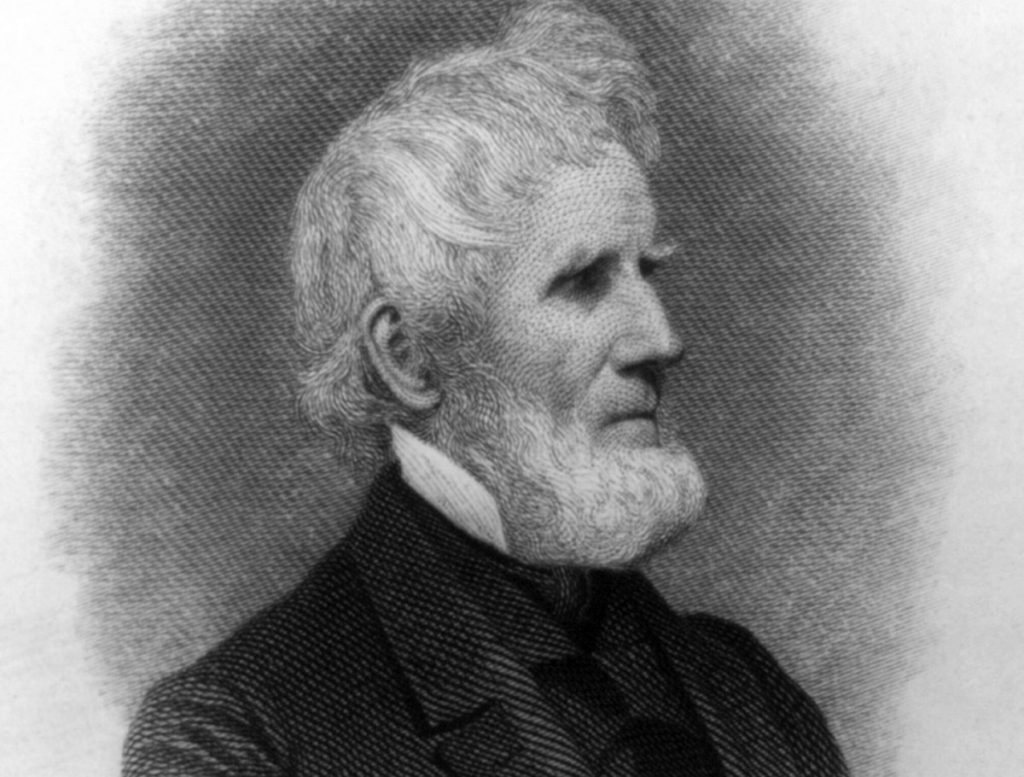

Lewis And Arthur Tappen

Arthur Tappan (pictured above) and his brother Lewis were silk merchants with an office at 122 Pearl Street. The Tappans were reformers and moralists. To learn about the character and reliability of his customers, Lewis Tappan created a network of informants, which later became a credit rating company. They were also abolitionists — they were founding members of the American Anti-Slavery Society, were part of the Underground Railroad, and helped organize the legal defense for the enslaved Africans who participated in the mutiny onboard the slave ship La Amistad. For their efforts, the Tappans were frequently threatened with ruin and death.

New Amsterdam

Wall Street famously got its name from the physical wall that fortified New Amsterdam in the 17th century, in an effort to protect Dutch colonizers from English attacks. The wall extended all the way across the lower part of the island, from the Hudson River to the East River. It was built in part by enslaved Africans owned by the Dutch West India Company, working alongside free Black and white inhabitants of New Amsterdam. Although the people enslaved by the company had certain rights, like being able to testify in court, own land and marry they were required to provide labor at the Company’s request and their children were not free. While the wall they erected is long gone, you can see recently-installed wooden pavers that mark the footprint of where it once stood.

African Burial Ground

One of New York City’s major Colonial-era sites, the African Burial Ground was active until 1784, with as many as 15,000 free or enslaved Africans interred below ground. Though the institution of slavery was officially abolished in New York on July 4th, 1827, enslaved persons were still held in New York beyond that date. The burial ground makes up nearly six acres, and dates back to the mid-17th century. Archeologists discovered the burials in the early 1990s while digging in advance of a new federal office building’s construction. After a series of protests by Black communities and others against the mistreatment of both the buried and the larger site — and the resulting Congressional hearings — the site was designated officially as a city, state and national landmark. The proposed federal building was still constructed, but its footprint was modified to preserve the burial ground. Selected via a national competition, architect Rodney Léon’s proposal for a monument to the burial ground was completed in 2007. The burial ground is the largest known excavated African cemetery in North America.