Wall Street “Was Literally Built for Men”: Author Paulina Bren on “She-Wolves: The Untold History of Women on Wall Street”

Early on in “She-Wolves: The Untold History of Women on Wall Street,” author and historian Paulina Bren sets the scene of a consequential spring day in 1762. In it, 24 people — brokers and merchants, men of means — gather under a buttonwood tree outside 68 Wall St. Here, they sign a document outlining rules for trading stocks: de facto birthing the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and establishing Lower Manhattan, as Bren writes, “as the beating heart of American capitalism.”

The men who wrote and signed the Buttonwood Agreement, for all of their ambition and belief in the great potential for the future, simply could not conceive of the idea that women would one day engage in this financial world they had created. Centuries later, Muriel “Mickie” Siebert, the first woman to own a seat on the NYSE, would discover this truth in a frank, telling way: on the members’ luncheon floor of the exchange, there was no women’s restroom. Before her, there was never a need for one.

“She-Wolves” tells the stories of female pioneers in a man’s world, tracing the footprint of women on the trading floor. From the 19th-century clairvoyant sisters who became the first female stockbrokers, to Siebert earning her seat on the exchange in 1967, to the shoulder pad-clad powerplayers of the ‘80s, Bren lets these oft overlooked women show their teeth.

Ahead of our November 21 LM Live event with Siebert Financial, we talked to the author about her book.

Much of the critical praise for “She-Wolves” highlights how well-researched and detailed your accounts of Wall Street’s pioneering women are. Could you start by telling us a bit about your process of doing research and finding sources for this book?

Well, there was initial shock when I discovered just how meager the sources were. From writing my previous book, “The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free,” about the famous women-only residential hotel on the Upper East Side, I was already accustomed to the notion that women’s histories are really hard to write because the sources are scarce. So I approached “She-Wolves” with this knowledge, and yet the dearth of sources was still shocking. Even a simple Google search didn’t reveal any major female players prior to the 2000s — other than the famous Muriel “Mickie” Siebert, of course.

A saving grace in all of this was an oral history archive that the New York Historical Society created about a decade ago, called “Remembering Wall Street: 1950–1980.” They commissioned oral histories of 50+ movers and shakers from Wall Street during these three decades. Unsurprisingly, about 50 of the interviews are with men and only five with women. But these five women were a starting point for me: I ended up bringing in three of them as characters in my book and re-interviewing two (one had since passed).

The HistoryMakers oral history archive, dedicated to prominent Black Americans, was also a terrific source for the story of Marianne Spraggins, even as I also had the chance to interview her myself. So these were starting points for my research.

“She-Wolves” weaves together a great number of individual women’s accounts against the epic backdrop of 20th century history — the 1929 financial crash, World War II, the Civil Rights and Women’s Liberation movements all informed the story of women on Wall Street. With all of these incredible characters and huge historical moments to dive into, what sparked the initial inspiration for this project?

I love to write collective biographies that are also sweeping histories which tell us so much more than one individual life can. That was the case with “The Barbizon,” which begins in the 1920s when the hotel is built, and carries through into the 2000s when it becomes a luxury condo building. And in fact the idea for “She-Wolves” came from that.

When I started, I was not particularly interested in finance, and I knew little about Wall Street, but it was clear to me that as much as the residents of the Barbizon Hotel (among them Grace Kelly, Sylvia Plath and Joan Didion) embodied a certain type of New York, by the late 1960s women had moved on from what the Barbizon had to offer. And I was curious where they had moved on to, what kind of young woman could be said to now embody a very different kind of city. I figuratively (and in the case of one character, literally) followed them from the Barbizon down to Wall Street.

When describing the atmosphere around Wall Street in an early chapter of “She-Wolves,” you mention how men often would not extend social niceties to women — i.e., removing their hats in elevators — in the Financial District as they would in other parts of the city. You write, “below Canal Street, it was defiantly a man’s world.” Can you expand on that line, and speak to how true it was in a literal sense?

Wall Street was literally built for men. It’s why I discuss women’s bathrooms at various points in the book! These women who finally arrived on the stock exchange floors — and even at the Wall Street Journal — found that there was perhaps one tiny bathroom that had been built for the occasional female visitor. Wall Street’s iconic Mickie Siebert battled with the NYSE to put in a bathroom near the Luncheon Club. She and others finally got one installed twenty years after she was the first woman to buy a seat on the NYSE in 1968. And she did that by threatening to bring in port-a-potties!

The book makes it clear that the women who dared infiltrate the “man’s world” of Wall Street did so at a high cost. But the cost was inarguably higher for Black women, who had to face racial discrimination in addition to gender discrimination, both in higher education spaces and in the workplace. What unique positions were people like Lillian Lincoln Lambert, the first African-American woman to graduate from Harvard Business School, or Marianne Spraggins, the first African American female managing director on Wall Street, put in that their white contemporaries were spared from?

Marianne Spraggins, who arrived on Wall Street at the very start of the 1980s, abandoning her job as a New York law professor because she felt that Wall Street exuded a fascinating sort of power and that a Black woman needed to be there to represent, said that it was actually harder to be a woman than to be Black on Wall Street. But it was hard any way you looked at it. Black women hired during the ‘80s and ‘90s (and most likely later, too) were often cruelly referred to as “twofers,” because a firm could then cross off two diversity and equality hires in one go.

As for Lillian Lambert, she was faced with an insurmountable roadblock when she showed up at the Harvard Business School in 1967, having no idea that she was in fact the first Black woman to attend, and this was only four years after the first class of eight women were allowed into the full two-year MBA program.

For all the women there, regardless of race, recruiting season in the spring of their second year was torturous because they were often laughed out of interviews, told that the firm wasn’t hiring women, or else had hired “one” two years before and were waiting to see how it went. But for Lillian, this was further exacerbated by her understandable feeling that she didn’t belong. And so even with a Harvard MBA, instead of using the invaluable network, she was combing through the help wanted ads in the newspaper.

A huge hurdle for the early she-wolves of Wall Street was the abundance of men-only spaces in 20th century New York — the executive dining halls and exclusive clubs where business happened behind doors closed to women. Was there any way for an ambitious woman to break into these heavily sequestered spaces?

Honestly, they couldn’t do anything about the many “No Ladies” signs posted throughout the Wall Street area (and elsewhere in NYC) until finally a city law simply forbade this. And if they were allowed inside some clubs, in many cases they were only permitted to enter through what was known as “the ladies door” around the back: in a sense, being brought in like the delivery personnel.

One of my favorite stories is of a woman asked to give a talk at a lunch meeting, but she couldn’t get inside the venue as a woman and so she had to climb up the fire escape. The men gathered to hear her speak helped her through the window, and then when she was done, down she went again the same way she’d come.

“She-Wolves” returns often to the story of Muriel “Mickie” Siebert, the first woman to own a seat on the NYSE. Her path up Wall Street was a mix of fierce ambition, perseverance and good luck. What about her journey drew you in the most?

It’s hard not to be drawn to her, and I feel she’s finally getting the recognition she has long deserved. I’ve had many readers of “She-Wolves,” which only came out two months ago, write to tell me that they knew Mickie personally and how remarkable she was, and how she helped other women (and men). She was a force of nature, and she was willing to be herself when on Wall Street, the pressure to blend in, to “act like a man,” was enormous. I also love that in her later years, when her offices were in the Lipstick Building, on the same floor as the Ponzi-scheme conman Bernie Madoff, her Chihuahua called Monster Girl would have a barking fit whenever they walked past his office. Clearly, she even had a dog with great instincts.

In popular culture, the most represented era of Wall Street tends to be the 1980s. Why do you think this time period has such cultural staying power?

The money, the money! And, yes, the shoulder pads, and the power suit, which were part of the whole atmosphere of money and the consequent power that came with it. I think also this testosterone-centered decade has been very appealing to both filmmakers and fiction writers. But inevitably one asks: “Where are the women?” They’re only there ornamentally, if at all. That was another reason it was vital to write “She-Wolves,” to offer a counterpoint to the pop culture depictions that we know so well.

In between the big historical moments the book covers, there are dozens of small details that further humanize the people in its pages. Are there any little moments from these women’s stories that have really stuck with you?

So many. But one of my favorites is [the story] of Louise Jones, who was found abandoned as a newborn in a phone booth on the Upper West Side, and then grew up in the housing projects on Staten Island. When she arrived on the floor of the NYSE for the very first time in the early 1980s, an eager and fresh-faced seventeen-year-old in a bright orange shirt, she felt for the first time in her life that she could finally breathe. She loved it all: the noise, the chaos, the possibilities suddenly before her.

There’s a generation of people working on Wall Street — many of them young women — who probably don’t know the names or stories of many of the pioneers profiled in “She-Wolves.” What do you hope this new cohort of Wall Streeters takes away from your book?

That they’re part of a history, a rich history. That there’s a legacy here that they’re building on, and that they can’t know which way is forward if they don’t stop to take a look at the past.

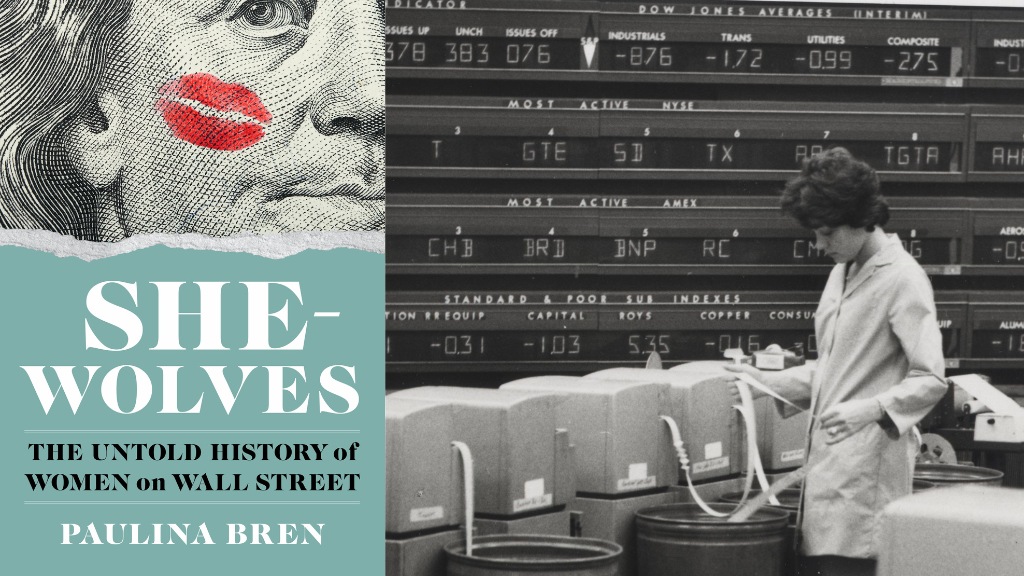

main image: Author photo courtesy Paulina Bren / Stock market image courtesy New York Stock Exchange

Tags: feature, interview